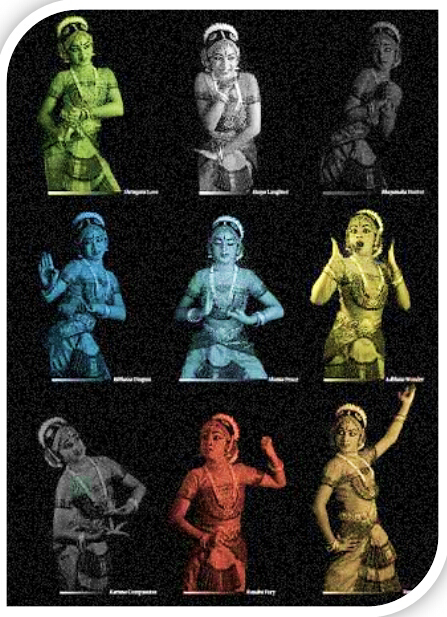

The Pathetic Sentiment

Grief (Śoka), arising from the loss of a kindred, immense wealth, or an insurmountable difficulty, transforms into the Pathetic sentiment (Karuṇa-rasa) when expressed through its Vibhāvas, Anubhāvas, and Sañcārībhāvas. The substrata (ālambhan vibhāvas) of this sentiment include the deceased kinsman, lost object, or worst calamity alongside the sufferer. It is aroused by references to the lost person's virtues, conversations about them, the sight of their belongings, visiting their residence, occasions where their absence is deeply felt, anniversary commemorations, offering libations, and similar scenes that rekindle sorrow, serving as excitants (uddīpana).

The consequences (anubhāvas) of grief manifest in the sufferer's squalor, shedding of tears, shouting, dullness, and choking of the throat. Additionally, disgust, swoon, sadness, anxiety, uneasiness, moroseness, and stupor function as ancillary feelings in Karuṇa-rasa. Moreover, paleness, shivering, change of voice, and stupefaction are self-existent states that visibly appear in the aggrieved individual, further intensifying the Pathetic sentiment in dramatic expression.

The Furious Sentiment

The Furious sentiment (Raudra) in Hinduism, rooted in rage and conflict, is prominently exemplified by Bhima’s violence and Duryodhana’s aggressive insults toward Krishna, reflecting jealousy and agitation as key elements in character interactions. This sentiment is particularly depicted in dramatic confrontations, such as the interactions between Chanakya and Chandragupta, and serves as the primary emotional force in works like Tripuradaha, where characters display intense anger. In Vyayoga, it is considered one of the required excited sentiments, portraying passionate and intense emotions.

The Raudra sentiment has its foundation in the dominant state of anger and originates from Rākṣasas, Dānavas, and haughty men, often arising from fights. It is triggered by determinants such as anger, rape, abuse, insult, false allegations, exorcism, threats, revengefulness, and jealousy, leading to violent actions like beating, breaking, crushing, cutting, piercing, taking up arms, hurling missiles, and drawing blood. On stage, it is represented through consequents such as red eyes, knitted eyebrows, defiance, biting of lips, movement of cheeks, and pressing one hand with the other. Additionally, its transitory states include presence of mind, determination, energy, indignation, fury, perspiration, trembling, horripilation, and a choking voice, making it a highly dynamic and dramatic sentiment in Hindu theatrical tradition.

The Heroic Sentiment

The Vīra rasa or Heroic sentiment is associated with superior individuals and is fundamentally based on utsāha (energy). It is created by vibhāvas (determinants) such as presence of mind, perseverance, diplomacy, discipline, military strength, aggressiveness, reputation of might, and influence. The anubhāvas (consequents) of this sentiment include firmness, patience, heroism, charity, and diplomacy, while its vyabhicāribhāvas (transitory states) comprise contentment, judgment, pride, agitation, energy (vega), ferocity, indignation, remembrance, and horripilation.

In Sanskrit drama, Bhavabhūti masterfully portrays Vīra rasa in the third act of Mālatīmādhava, where Makaranda heroically rescues Madayantikā from a tiger, and again in the fifth act, where Mādhava showcases his bravery by snatching Mālatī from the clutches of Aghoraghaṇṭa, who was about to kill her. On stage, heroic sentiment is depicted through consequents such as firmness, patience, heroism, charity, and diplomacy, emphasizing the qualities of a valiant and superior character. This dynamic and noble sentiment, deeply rooted in energy and courage, forms an essential aspect of dramatic representation in Hindu theatrical traditions.

The Terrible sentiment

The Bhayānaka rasa, or Terrible sentiment, is rooted in the permanent mood of fear and evokes a profound sense of terror in the mind. It arises from determinants (vibhāvas) such as hideous noises, the sight of ghosts, panic, anxiety triggered by the untimely cries of jackals and owls, desolate forests, empty houses, the sight of death or captivity of loved ones, and discussions surrounding such distressing events. On stage, this sentiment is depicted through consequents (anubhāvas) like trembling hands and feet, horripilation, a change in complexion, loss of voice, and overall physical unease.

Additionally, its transitory states (vyabhicāribhāvas) include paralysis, perspiration, a choking voice, fear, stupefaction, dejection, agitation, restlessness, inactivity, epilepsy, and even death, all of which heighten the overwhelming sense of dread. The Bhayānaka rasa plays a crucial role in dramatic performances, effectively portraying the raw and unsettling experience of fear through expressions, movements, and psychological distress.

The Odious sentiment

The Odious Sentiment, known as Bībhatsa in Sanskrit, is one of the nine Rasas or the “soul of drama,” as described in the Viṣṇudharmottarapurāṇa, an ancient Sanskrit text covering diverse cultural subjects, including arts, architecture, music, grammar, and astronomy. This sentiment arises from jugupsā (disgust), which is its sthāyibhāva (permanent state), and is primarily evoked by the sight of something repulsive or revolting. The Nāṭyaśāstra also acknowledges jugupsā as the foundation of Bībhatsa rasa, emphasizing that this sentiment is expressed through physical reactions, such as the shaking of the nose, which conveys a strong feeling of aversion or disgust in dramatic performances.

The Marvellous sentiment

The Marvellous Sentiment (Adbhūta Rasa) emerges from the mental state of surprise and is evoked by witnessing something extraordinary or unexpected. It arises from ālambaṇas such as wonderful objects, astonishing incidents, or seemingly impossible feats, like those performed by jugglers. The surrounding circumstances further heighten this feeling of awe. This sentiment is expressed through physical reactions like an unwinking gaze, widened eyes, interjections, and twisting of fingers, all of which convey a sense of amazement. Additionally, stupor, perplexity, dumbfoundedness, and flurry act as ancillary emotions that enhance the Adbhūta Rasa. It is often accompanied by self-existent states such as stupefaction, a flow of tears, horripilation, and a choked voice, all of which intensify the sense of wonder in dramatic expression.

There are critics who have provided different criticisms on the Rasa Theory, including Bhatt Lullat, Shree Shankuk, Bhatt Nayak, and Abhinavgupt.

Bhatt Lullat states that Rasa is not created but rather revealed through the process of Utpattivada (the theory of emergence).

Shree Shankuk argues that Rasa is experienced by the spectator, which is explained through Anumitivada (the theory of inference). He categorizes perception into four types:

1. Samyak Pratiti (Accurate Perception) - When the perception is correct.

2. Mithya Pratiti (Incorrect Perception) - When the perception is wrong.

3. Sanshay Pratiti (Doubtful Perception) - When the perception is uncertain.

4. Sadrushy Pratiti (Analogous Perception) - When the perception is similar to the real thing.

Later, Bhatt Nayak states that Rasa is experienced. When the actor, actress, and spectator share a common emotional experience, it leads to Sadharanikaran (universalization), also known as Bhuktivada (the theory of experience).

Abhinavgupt states that Rasa is experienced as a mistaken identity, where the knowledgeable person experiences a state of relaxation, and this is known as Abhivyanjana (the theory of expression).

"प्रकाशानन्दमयज्ञानिनि विश्रान्तिः"

These theories provide different perspectives on the Rasa Theory, contributing to a deeper understanding of aesthetics and emotional experience.

Thank You !

References :

Comments

Post a Comment